Enabling functions in an organisation are critical to performance. Yet we regularly get the plug-in model wrong. We leave users of services feeling unsupported and managers frustrated. Or we go too far the other way and let managers dictate their preferences even though they are not in the best interests of the organisation. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to how to set up your enabling functions. This case study looks at one organisation’s journey to get the balance right and the solution they came up with.

what is an enabling function?

The ones that quickly come to mind are things like our people functions – talent management, recruitment, payroll. Or procurement support, so you can get the right specialist or consulting expertise when you need it.

But the rule setting functions are equally part of the enabling suite. Things like delegations and governance functions, or risk and audit. Some of the common characteristics are it:

- usually has an internal client (within the organisation or the parent group);

- either helps someone else do something (provides a service) or sets out how someone else should do something (pathway and process);

- often has a corporate wide purview; and

- usually has low visibility to the primary external client/market.

Our case study

Organisation xyz was experiencing typical symptoms of a less than ideal business division:corporate relationship. High dissatisfaction reported from business area owners. Frustration in corporate areas at the lack of ownership taken by managers and compliance with corporate policy. Services were poorly defined and monitored, but where there was information available the performance was average at best, and often highly variable across service channels and interactions.

After a series of structured discussions, onsite observations, data diving, and document reviews, the three most valuable challenges to solve emerged:

- How do we ensure client divisions trust the advice coming from corporate?

- How do we get on one page about the key services the business needs to perform (within a tight budget environment)?

- How do we help everyone be more self-sufficient over time?

the solution

challenge 1: Low trust, low compliance

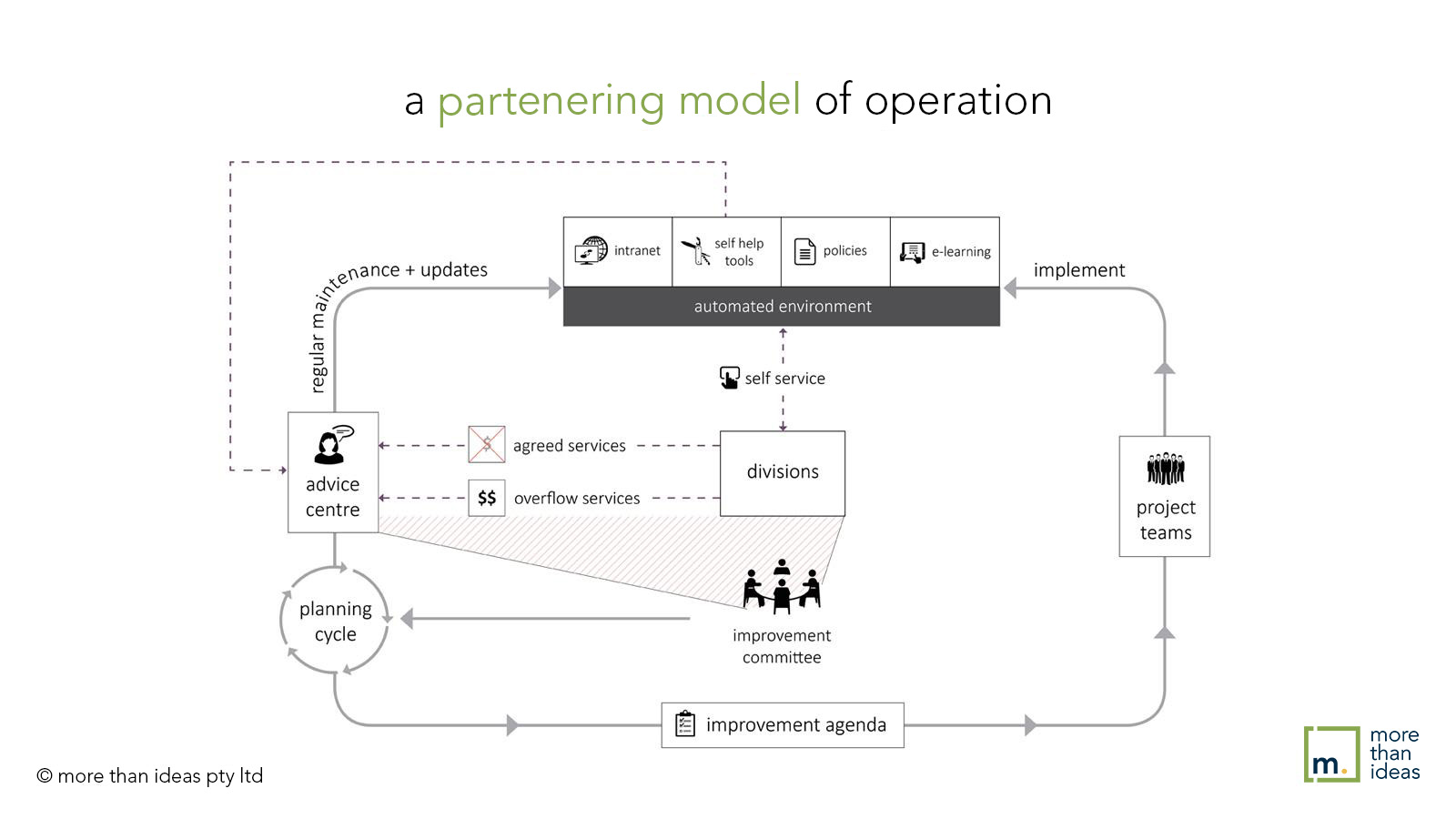

In this case, a governance-led solution was developed. To build co-ownership, the governance around the corporate service suite was changed from line management to an improvement committee with client representatives, users (line managers), and service owners. This group was tasked with ensuring performance to agreed service standards, managing the improvement agenda and the improvement budget.

The position of client representative and user rotated across the business on a 12-month basis with a one quarter overlap for continuity. In addition, the business units were required to provide resources and/or budget (co-funded by corporate) to the improvement budget as well as resources.

Finally, the KPI framework was to balance service (eg response time, resolution type etc) and user indicators (eg information provision, implementation of agreed actions, completion of manager-led activities) and the contribution from the client. So service failure was no longer an unfounded us-and-them conversation. It was evidenced and diagnostic, and acknowledged the business performance objective behind any service interaction.

challenge 2: service gaps and mismatches

Org xyz was very nervous about implementing service-level agreements internally. They didn’t like the impact they might have on their culture and were concerned they might counteract their value set. But, equally, the business areas were very frustrated at the inconsistency of services offered, and the lack of responsiveness when they had a real time critical need for support.

The approach to solving this challenge was through service design:

- A base-level service suite was developed, based on available budget and likely resource intensity. This was to be funded from a corporate allocation without charge to the business on a service basis, to encourage a collaborative relationship between corporate advisory staff and the business. The service suite included self-service tools, but wasn’t strictly hierarchical for the first 12 months for team managers (ie a manager could choose to ring and have a conversation rather than go through a forced choice channel like FAQs or a bot or a service request).

- A set of ‘on request’ services were scoped out and made available on a pay-for-service basis. This allowed business units to decide to use some of their operating budget to access bespoke quick response services if they were important enough. The pay barrier ensured demand control, whilst giving businesses the surety that when they knew something was urgent they could get support.

challenge 3: self-sufficiency

Org xyz had strict corporate overhead benchmarks to hit that made cost reduction over time a key priority. But they also had a culture of low self-sufficiency in things like people management, IT solutions, business improvement and procurement.

The solution in this case was to use two pathways to establish an automated self-service environment. The first was improvements driven by the advice centre who had a certain proportion of work time quarantined to build and implement automated solutions. The second was through programmed improvements overseen by the improvement committee, where the solutions were developed by a mix of corporate and business staff and supplemented by external skills as required. Clear targets were set to transition the service model from high-cost high-contact models (such as business partnering and phone support) to low-cost high-convenience models (like self-service payroll portals where employees could answer queries like their leave balance, pay conditions, and bank details).

the takeaway?

Each organisation is different and your solution should be tailored to reflect these specific contextual factors. However, coming up with the most valuable challenges to address first will greatly improve the chances that you will get the right ‘plug and play’ outcome for you.